Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a ceasefire deal to end the war for control of Nagorno-Karabakh enclave last month, after a series of Azerbaijani victories in its fight to retake the disputed enclave. The deal also guarantees a land corridor linking Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, which will be monitored by Russians (2,000 peacekeepers and 100 armoured personnel carriers), besides staggered withdrawal of Armenian forces from Azeri districts surrounding the enclave by December 1.

The agreement is much to the displeasure of Armenian people, although it has prevented many innocent killings in the crossfire for the time being. The conflict is one of the latest ones, with effective use of some modern arsenal like drones and a mix of hybrid warfare combined with political power-play. It has many strategic and military inferences/lessons applicable globally in modern warfare. It also generates some questions, which global bodies and some countries will find it difficult to answer.

ARMENIA AND AZERBAIJAN

The deal marks an end to six weeks of fierce clashes over Nagorno-Karabakh, an ethnic Armenian region of Azerbaijan that broke away from Baku’s control during a bitter war in the 1990s. Karabakh declared independence nearly 30 years ago, but the declaration has not been recognised internationally and it remains a part of Azerbaijan under international law. The dispute has continued to simmer over decades as the majority of inhabitants in the enclave are Armenians. Azerbaijan and Turkey may have some reasons to celebrate, but with mounting anger in Armenia and dissatisfied residents of Nagorno-Karabakh, the duration of the peaceful period remains uncertain. Understandably Armenian leadership was left helpless, with no choice but to save further casualties, after the loss of the region’s strategically vital town Shusha, so located that it overlooks Nagorno-Karbakh’s main city Stepanakert and the main road linking Armenia to the enclave. Armenians feel let down by poor response from its allies and Russia and find themselves plunged in internal turbulence.

STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS

The conflict exposed the weakness of NATO and European Union to help its ally at the time of crisis. The most important strategic impact has been a boost to radicalised Islam, emerging out of Erdogan’s overambition to grab Islamic leadership to become Caliph, besides reviving Ottoman Empire and seek control of oil and gas pipelines in the region. Although the region had a history of hostilities, the recent one was allegedly triggered by active support of Erdogen.

The fact that he openly supported it with conventional weapons and transported non state actors from like-minded countries like Pakistan and Syrian mercenaries/terrorists, to fight on behalf of Azerbijan, which helped it to win the conflict makes Erdogen’s position stronger in countries and groups believing in radicalised version of Islam. The immediate impact is visible in the EU getting into the grip of radicalisation faster than they thought, as it watched the massacre of Armenian Christians, without punishing Turkey so far.

The conflict exposed NATO as a divided house, incapable of taking decisive action against threat to its allies. Notwithstanding the strategic location of Turkey and NATO assets deployed there, it’s time to put its house in order, by punishing its problem child, Erdogen. NATO failed to even give a threat of expulsion to Turkey, despite its actions in this conflict and opening a friction point with Greece in Mediterranean Sea. With the US and France embroiled in internal affairs, NATO seemed leaderless and directionless. This raises a bigger question whether the era of alliances is over in an interconnected world, and the viability of democracies getting together in other regions like Indo-Pacific to counter Chinese threat to the world has a chance or otherwise?

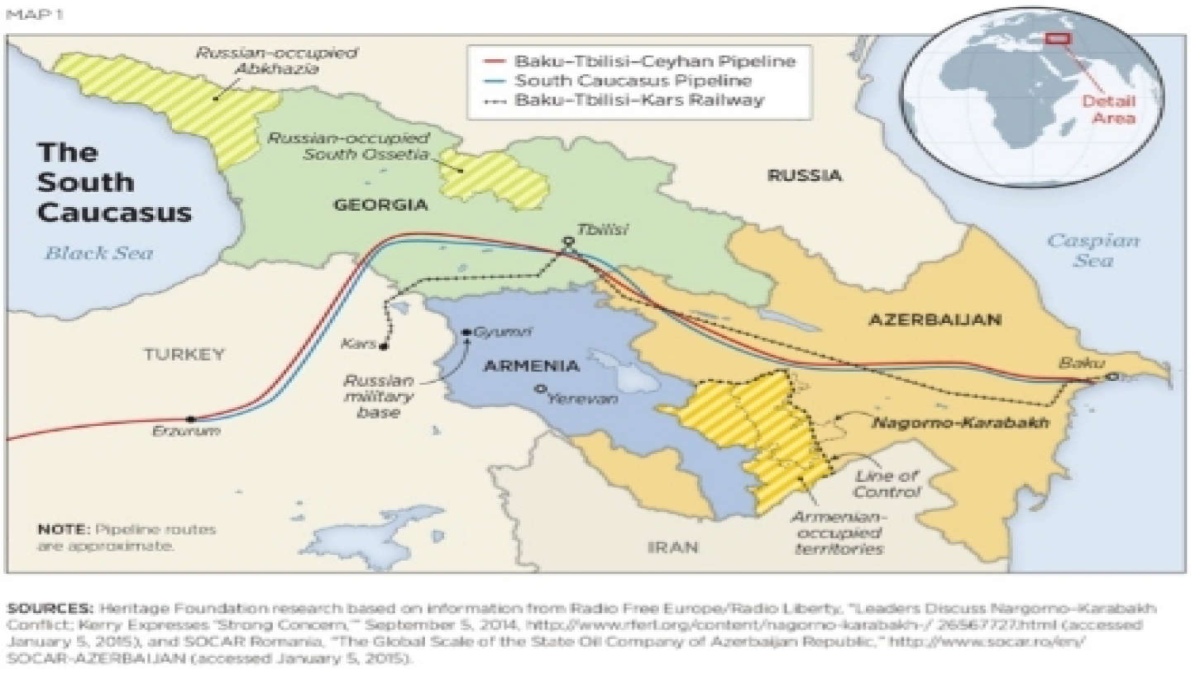

The biggest loss of reputation is for Russia, which chose to play neutral, selling arms to both the parties to the conflict, despite a military pact with Armenia and a base there. It insisted not to get involved in the conflict with Azerbaijan, unless Armenian territory itself came under threat. It exhibited its weakness to control Erdogen, stop genocide of people of its erstwhile states and induction of various radicalised non state actors of Syria fighting against Christians in the region. Promoting one sided peace agreement and deploying Russian peacekeepers in the disputed Caucasus territory guaranteeing linking land corridors to Nagorno-Karabakh (besides protecting Russian oil and gas pipelines), coupled with Armenian withdrawal is a response, too little, too late.

China, which was playing neutral, as both countries are partners in BRI, could emerge as one of the main beneficiaries by gaining a new route for the BRI, besides leverage over Iran during crucial negotiations. The corridor between Nakhchivan and Azerbaijan would offer Beijing a second route to Europe in the South Caucasus bypassing Iran.

MILITARY LESSONS

The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict highlighted that hybrid war is a reality, even in conflicts between states. The idea of hiring mercenaries/terrorists on religious lines is viable, as exhibited by Turkey and Pakistan; hence having a terror industry makes sense with adequate takers to hire their services. Recently Human Right Watch has reported ill treatment of Armenian Prisoners of War, in violation of Geneva Convention, which is quite normal, when terrorists are involved. This is a dangerous trend which must be checked by the global community.

The conflict highlighted the air battle being influenced maximum by use of drones. The precision strikes by drones on all types of targets were game changers. The future wars will demand much higher reliance on drones to achieve desired effects without fear of human casualties. Drone warfare including countering drone threat from adversaries, has to be an essential component of technological warfare. Drone swarming, drone surveillance and many such uses including strategic bombing may be possible through drones in future. In Indian context a major effort to boost these capabilities will be required.

Although President Putin said: “the agreements reached will create the necessary conditions for a long-term and full-format settlement of the crisis”, but I have my doubts because dissatisfied Armenians and unpunished Turkey, cold shouldering by EU and NATO, is a recipe for further troubles, although the guns are silent for the time being.

Maj Gen S.B. Asthana (Retd) is a strategic and security analyst, a veteran Infantry General with 40 years experience in national & international fields and UN. The views expressed are personal views of the author, who retains the copyright.