Today, 11 Nov 20, is the anniversary of Armistice Day, the day World War 1 ended, more than a century ago, in 1918. Many countries around the world also commemorate this day as the Remembrance Day. India was involved in a significant way in the war but Indian participation has not been given adequate recognition in the annals of history. While there have been some welcome recent initiatives, especially in the years marking the centenary of the Great War, there has been a tendency to either overlook our role or be diffident about it, in part because many people feel it was done for a foreign Flag and, therefore, not worthy of attention. In fact, sadly, many Indian scholars and intellectuals actually look down upon this effort. This neglect or disdain has, therefore, resulted in near obliteration of this chapter from our memory, even though it has happened relatively recently.

While the debates about actions taken ‘at the behest of Colonial power’ are endless, India saw 1.5 million soldiers being involved in the war and give an excellent account of themselves on the front-lines. 74000 Indian soldiers lost their lives and many more were injured. Therefore, it should be possible to venerate and respect that part of the war while negotiating the dialogue about the ‘foreign cause’. In this regard, Indian Navy’s approach may be instructive. Let us take the case of a little-known event of World War I in East Africa, involving Indians. It, in some ways, also connects to our present.

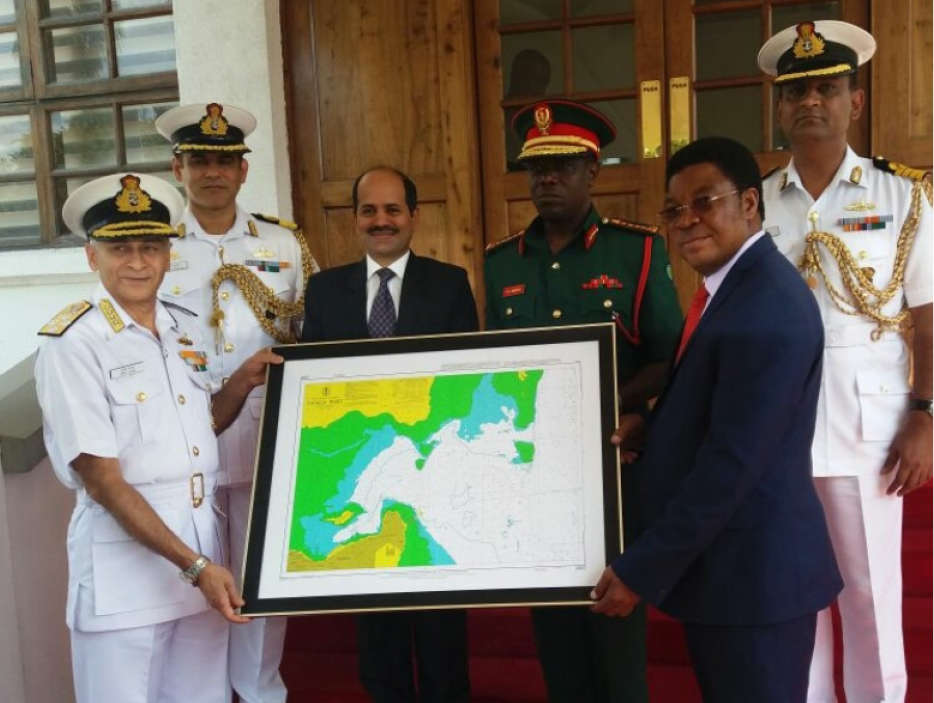

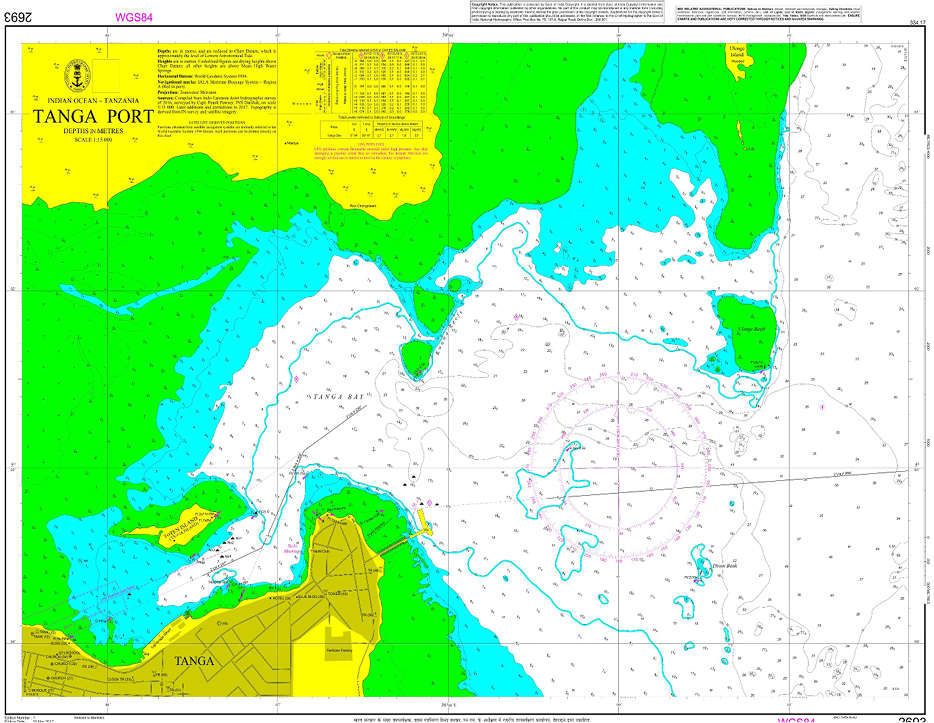

On 28th July 2017, while on an official visit to Tanzania, the Chief of the Naval Staff, Admiral Sunil Lanba presented a chart of the port of Tanga (in northern Tanzania), to Hon’ble Kassim Majaliwa, the Prime Minister of that country. This chart (as maps in the maritime world are called) was the result of an extensive hydrographic survey undertaken by an Indian Survey Ship, demonstrating not only our prowess in hydrography (the equivalent of surveying on land but hydro ships do much more) but also the contribution of Indian Navy to our international cooperation engagements.

Photo Credit: Taken from the Book “Tanganyikan Guerrilla- East African Campaign 1914-18” written by Major JR Sibley.

Indians, by and large, are either uninterested or unaware of East Africa, despite both geographical proximity and historical antiquity playing an important role in our centuries long association. While the knowledge of our participation in the WW I is scant, that of the East African theatre is even less known. Not many may be aware, but Tanga has a war historical connection with India. This tale relates to that.

Within months of war breaking out in Europe, it spread to Africa where the belligerents had colonial interests. British Admiralty was eyeing Tanga, the busiest port in the East African coast under German control. (Do recollect that Tanzania or more specifically Tanganyika then was a German colony). The idea was simple. By taking over Tanga, Britain could not only block German trade in/to Africa but could also further target the Usambara railway line, thus hitting at the heart of German possessions in Africa. This would enable British control of whole of East Africa. In order to do this, an amphibious assault was planned on Tanga. To be fair to the British, the Germans had already moved across the border and seized Taveta in Aug 1914. Also, the greater German strategic goal was a sound one – to keep a bulk of British troops occupied in defending their colonies so as to reduce their numbers in the European theatre.

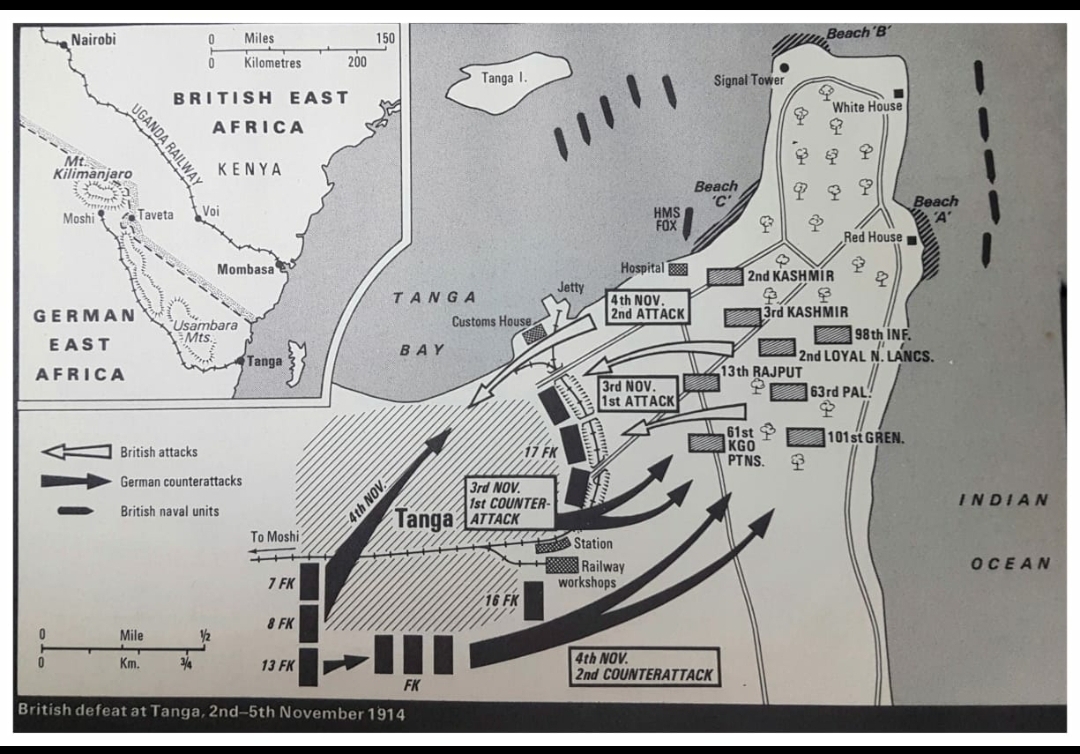

While the Royal Navy provided the ships for this assault on Tanga, the manpower or the Army troops were predominantly from the Indian Army. The 8000 strong Indian Expeditionary Force B led by Maj Gen Arthur Aitken, consisted of the 27th Bangalore Brigade (which comprised 2nd Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, 63rd Palamcottah Light Infantry, the 98th Infantry, the 101st Grenadiers, 28th Mountain Battery RA, the 25th and 26th Companies Faridkot Sappers and Miners and 61st KGO Pioneers) and the Imperial Service Brigade (which comprised 13th Rajputs, the Gurkhas of the 2nd Kashmiri Rifles, a half battalion of 3rd Kashmir Rifles and half battalion of 3rd Gwalior Rifles). After the assault, the Force was to link up with Expeditionary Force B which was already pushing forward to Moshi (at the foothills of Kilimanjaro). Force B consisted of 29th Punjabis, Imperial Service Battalions made from the states of Bharatpur, Kapurthala, Jind and Rampur and the 1st battery of Calcutta Volunteers.

The assault was launched on 02 Nov 1914 but turned out to be a big failure. While total surprise could not be achieved as a local truce agreement to not attack each other’s ports had to be called off and announced to the Germans, the British were facing a light opposition consisting of only one company of East African askaris (security guards). However, in the the slow and lumbering advance of the operation, in part due to being deceived about the harbour being mined, the British controlled troops failed to progress, allowing the opposition under Lt Col Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (let’s call him Col LV for short) to recoup, bolster his strength with the addition of six more companies and put up stiff resistance. The entire Battle reads like a tragicomedy. You can Google for details, but suffice it to say here it was actually a case of both sides committing blunders galore with the British excelling at it. The battle of Tanga is also often called the ‘Battle of Bees’, since in another tragicomic incident, several huge beehives were disturbed by both sides in the battle and they in turn descended on the troops in a swarm injuring and hurting many. Many British stories talk of this as a fiendish German ploy but the truth was more prosaic. The agitated bees added to the X factor in the war.

For three days, the battle went on with 1000 in the German defence force, the Schutztruppe (largely colonial volunteers and native African soldiers, with very few German troops) and 8000 in the invading British Indian force. Fortunes fluctuated and in fact on the night of 04 Nov, when German forces briefly withdrew west to consolidate, Tanga was for the taking but Aitken did not press home the advantage. Determinedly, the smaller German force held its ground. Ultimately, the British, after incurring several losses, disarray in troops and staring failure, decided to call off the assault and evacuate the troops. On 5th Nov 1914, the evacuation was finally complete but the end result was messy. The casualty count, almost all Indian, was close to1000 with 360 troops dead, close to 500 injured and another 150 reported missing. The distraught and disarrayed troops in many cases fled leaving behind their equipment, arms and ammunition. In contrast, the Schutztruppe had 71 dead and 76 wounded.

Tanga, in many ways, was a disaster and there is no harm in saying so. In fact, British war history records it as one of their worst defeats. Tanga does not resonate of bravery like the other great episodes of WW 1 or 2 like Ypres or Flanders. It was not heroic like Haifa, not even a courageous defeat after a fierce fight like Gallipoli. There was none of the romanticism that was to be associated (later in WW 2) with Dunkirk. This was simply ignominious.

British writing makes it out that the Indian troops were unprepared and ill-trained. Perhaps there is a point there, but this was no fault of the Indians. Those that had been trained and equipped had already been sent to the European and Mediterranean theatres. Tanga was hurriedly conceived and launched with the residual troops in India forming a new expeditionary force. Major Roger Sibley, a British Army officer and writer brings out in his book on the East Africa campaign “the names of the Brigades were misleading as both brigades had been recruited from the length and breadth of India; both men and officers were strangers to each other and even more so to their new Commanders”.

Further, as we all know, in war, especially combat, it is the leadership that is mainly instrumental in the ultimate outcome. And the British leadership was, arguably, poor. Be it Aitken himself who was relieved of Command after this campaign or Navy Capt Francis Caulfield, the Captain of HMS Fox, the Royal Navy flagship, they showed lack of understanding of terrain and inadequate temperament. Several aspects stand out for poor planning – the journey to Mombasa and then Tanga on the ships done in a hurry, inadequate training, scanty intelligence, non-use of naval ships for gunfire support and Aitken’s disregard of the advice of his Staff Officers and the Commanders in Kenya who had a better knowledge of the local conditions. In contrast, Col LV proved to be a great leader. In fact, he remained the only German campaign Commander who was undefeated in the War and is considered a heroic figure in Africa. In fact, after the failed attempt at Tanga, the British attempted to attack Tanzania through Kenya from land, targeting the railway lines at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, once again involving several Indian troops, but Col LV could not be overcome.

Many commentators have echoed the description of WW1 as given in the book ‘In Flanders Fields’ where author Leon Wolff says “The First World War was undoubtedly the most horrible war ever fought, the most senseless, the most unimaginative in its strategy and for the men who found themselves in the trenches, the most hopeless”. This applies even more to Africa where, arguably, no great strategic purposes were served, save, possibly, the ‘prestige’ of the Colonial powers. In a book on ‘Command Failure in War – Psychology and Leadership’, the authors Robert Pois and Philip Langer, both Professors at University of Colorado-Boulder, have devoted a full chapter to the British Military in World War 1. Significantly, even they focus on Europe and ignore Africa completely. However, in their overall assessment of British Strategy they bring out that “with a few notable exceptions, the British war effort between 1914 and 1918 was characterised by a seemingly perverse commitment to stale, unimaginative tactics that were responsible for slaughters that would only be equalled only by those on the Eastern Front in WW2”.

Therefore, it could be argued that the dead and injured and missing from India were just as hardy and committed as their brethren elsewhere. It was simply their fate to suffer, as Soldiers often do, the consequences of things beyond their control. The dead in Tanga are a part of the more than 3000 Indian soldiers whose graves lie in various parts of East Africa. As most Indian soldiers were cremated and not buried, their names are mentioned not grave wise, but on long plaques in the many Commonwealth war graveyards that are located in Kenya and Tanzania. An important point that bears mention is that the East African theatre of war was very difficult from the European one. Maj Sibley writes “the campaign was fought mostly in ‘bush country’, which in fact was anything from open parkland to dense forest or thorn scrub. The physical and climatic hazards were arduous enough but coupled with dangers of rhinoceros, elephant, lion and crocodile, Command and Control became formidable tasks. The soldier also had to contend with the constant battle against mosquitoes, tsetse flies, jiggers and ticks, not to mention bilharzias from infected rivers and lakes”.

This military link between India and Africa is often not known or under emphasised in our national narratives. In fact, soldiers from India formed some initial component of the King’s African Rifles (today Kenya African Rifles) from the last decade of the 19th century and were disbanded around 1913, just before the war. As historian Thomas Metcalf in his book ‘Imperial Connections’ puts it “The Indian Army, then, made possible the expansion of the British Empire across territories as widely scattered as Malaya, East Africa and Mesopotamia”. Similarly, it is not known that Kenyan soldiers fought in the North East, in the Burma campaign in World War 2 and many died here. Post-independence, India continued the tradition in a new benign avataar of peacekeeping and many of our troops have played a most distinguished part in Peace Support Operations in Africa. In fact, the first ex NDA officer to be awarded a Param Vir Chakra was Capt GS Salaria, for operations in Congo in early sixties. During my tenure in Kenya, as the Defence Adviser in the Indian High Commission at Nairobi but accredited to East Africa, I tried my best to inform the local Africans, the Indian diaspora and other nationals, especially those from West, about these fascinating historical details.

That brings me to the present. In Oct 17, at the Goa Maritime Conclave eminent strategic affairs scholar Dr C Raja Mohan made the point that British colonial enterprise was undergirded by three important elements – the Royal Navy, the Indian Army and the carefully enmeshed government and administrative structures of envoys, regents, intelligence officials, collectors, police officials. He also rued the fact that a newly independent India looked inward and had neither the appetite nor imagination to view the world as the British did resulting in a loss of strategic space for India post 1947. He also inferred that it is only in the last few decades that we seem to have recovered our mojo as a regional or middle power.

Without getting into these debates on power theories and international relations, it can be clearly said that the Indian Navy has been playing a key role in our international engagements, especially in the past two decades. We are the best manifestation of an India that is looking outward again but we do so by invoking new benign paradigms. Instead of expeditionary operations we believe in foreign cooperation. Respect for each other, mutual partnerships, joint stake-holdership, non-invasive frameworks are the buzz words that characterise our initiatives, as brought out by Admiral Sunil Lanba in the same conclave. The same point was forcefully stressed just last week by Admiral Karambir Singh, the current CNS, at the NDC seminar, when he described the first line of effort of Indian Navy’s regional strategy as “Collaboration and Cooperation with partners” to be built on pillars such as ‘trust, interoperability and enhanced engagement’ among others.

Therefore, it was entirely appropriate that the site of a battle between colonial antagonists should become the very location of a new cooperative endeavour of a post-colonial world. Indian Navy’s hydrography standards are world class. By assisting the Tanzanian authorities in surveying the port of Tanga we gave a fillip to regional cooperation.

And the date that the Navy Chief presented the chart is significant. 28 July 2017. Do remember, 28 July 1914 was the start of World War 1. 103 years later, to the day, the CNS connected the dots of the history. And 106 years later, on Armistice Day, I hope as an amateur historian, that the Indian Navy’s grand gesture finally puts a closure to the disaster of that day.

We have indeed come a long way from Tanga.

PS – I understand that the Tanga amphibious campaign is studied and has been analysed in detail by the United States Command and Staff Course. Despite the time gap and the somewhat farcical elements of the battle, it continues to be relevant as a case study particularly for Expeditionary forces.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Cmde Srikant Kesnur is a serving navy officer with interest in contemporary naval history.