At around 1700 hours on Sunday, 17 December 1961, Governor General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva was addressing a teachers’ function at Vasco da Gama Hall in Goa, the Portuguese enclave on India’s western coast. A person walked up to him and whispered, “Sir, the Indian Army has arrived at our borders.” For a moment the Portuguese Governor General’s mind went completely blank.

The brisk Indian armed assault codenamed “Operation Vijay”, in a three-pronged advance with over 30,000 Indian troops was underway. By the early hours of Monday, 18 December, all the naval threats were effectively neutralised and the Indian Air Force achieved complete air supremacy. That day Goans woke up to the sound of explosions as the Portuguese Army blew up over thirty bridges to stall the advancing Indian Army. Hugely outnumbered the main Portuguese strength was concentrated in the capital Panjim (later Panaji). Consequently the city became the military objective of the Indian Army.

‘Meghna’ after the Bangladeshi river.

Rushing in the direction of Panjim was the Bikanerborn Rajput, Brigadier Sagat Singh along with his 50th Para brigade. The 42-yearold Brigadier was a remarkable commander who fought in the gruesome Second World War. He went on to become one-of-a-kind military mastermind that India produced. With indomitable fortitude and resolve Brigadier Sagat led the 50th Para brigade into the arena of war. Towering above everyone at six feet two inches, he had earned his “Para Wings” in record time by making four Para jumps in a span of two days, an astonishing feat at his age. The daring Brigadier ordered his men to take the smugglers route to enter Goa clandestinely. Notwithstanding the blasting of bridges, mines and culverts, the Indian troops still armed with WW-II era weapons surprised everyone. In a race against time they made a whirlwind advance against the Portuguese forces and streamed towards Panjim. On hearing the firing across the Mandovi river at Betim, the Portuguese flag in front of Palacio de Idalçao in Panjim was lowered and the white flag was hoisted to indicate surrender.

And thirty-six hours after the commencement of the operation at 0600 hours on Tuesday, 19 December, India’s 50th Para brigade crossed the river Mandovi along with the 2nd Sikh light infantry. They became the first Indian troops to enter Panjim and liberate the capital. Brigadier Sagat ordered the troops to remove their steel helmets and don their maroon berets. In the black and white archival news footage shot that day Goans can be seen waving Indian flags and welcoming the Indian soldiers. The official Portuguese surrender ceremony was conducted at 2030 hours on 19 December. Under the headlights of a car the official letter of surrender was signed by Governor General Silva and delivered to Major General K.P. Candeth. A few days later Ronald C.V.P. Noronha, an ICS officer, was transferred from Madhya Pradesh to Goa as the Chief of Civil Administration. An area of about 1,500 square miles on our western coast was reunited with India.

It was Brigadier Sagat’s audacious leadership that tilted the balance in India’s favour. Interestingly, Major General V.K. Singh in his book, Leadership in the Indian Army: Biographies of Twelve Soldiers, has recorded that Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Salazar had announced an award of $10,000 to anyone who captured and delivered the Indian Brigadier Sagat Singh to Republica Portuguesa. Inexplicably back home the Defence Ministry of India disallowed gallantry awards for the liberation of Goa.

Six years later, on Wednesday, 6 September 1967, seventy Chinese soldiers intruded across India’s northern border south of Nathu La located at 14,200 feet in Sikkim and were challenged by 2 Grenadiers, the battalion holding the defences. Thereafter, intrusions by the Chinese were reported on a regular basis.

Since the war in the Himalayas in 1962 the relations with China were strained. In June 1967 a diplomatic fracas erupted due to Chinese belligerence. Two Indian diplomats K. Raghunath and P. Vijai were unfairly accused of espionage and sentenced to “immediate deportation” by the Peking Municipal People’s Higher Court. The Indian Minister for External Affairs Mohammadali Carim Chagla was outraged by the public humiliation of our diplomats. In those adverse circumstances Indian diplomacy matched China at every step and eventually outmanoeuvred the adversary.

Three months later, the Chinese provoked India by crossing the line at Nathu La. At that time the Eastern Command of the Indian Army, post the 1962 debacle, was hesitant to incite the Chinese. The Command issued a directive to the Indian forces to vacate the border posts. Major General Sagat Singh, the General Officer Commanding, 17th Mountain Division in charge of that border since July 1965, disagreed with the order. He had walked along the crest line himself and was of the view that Nathu La comprised the natural boundary. Reacting to the intrusion in early September 1967 he ordered the building of a fence and asked his men to vehemently defend the remote Nathu La pass come what may. The Chinese mounted loudspeakers at Nathu La, and cautioned the Indians that they would suffer as they did in 1962, if they did not withdraw. On Major General Sagat’s instructions Indian loudspeakers broadcast tape-recorded Chinese language with counter messages.

On Monday, 11 September 1967, Lieutenant Colonel Rai Singh, Commanding Officer of 2 Grenadiers, was supervising the erecting of the iron pickets from Nathu La to Sebu La along the perceived border. The Chinese Political Commissar and his men arrived and objected to the laying of the wire. Lt Colonel Rai Singh had orders not to blink. An intense argument followed and resulted in a scuffle. This escalated into medium machine gun fire by the belligerent Chinese on the Indian troops. Outnumbered the Indian troops faced overwhelming odds against a ruthless enemy. Then with fierce fire, the Indian troops launched a counter-attack on the Chinese frontier guards. According to an official note issued by Chinese Foreign Affairs, “Up till noon, the Indian aggressor troops already killed or wounded 25 Chinese frontier guards.” The note added a clear warning, “Do not misjudge the situation and repeat your mistake of 1962.” It was actually the Chinese who had underestimated the Indian reaction.

On orders from Major General Sagat the Indian Army men stood their ground in brazen defiance. The Indian Army retaliated with their weaponry, and fought brutal hand-to-hand battles at the pass. In the end Nathu La Pass remained firmly in the control of the Indian Army. A few weeks later another attack at Cho Pass, northwest of Nathu La, was similarly repulsed. The Chinese forces met more than their match and eventually backed off. The New York Times in a news report on 1 October 1967 detailed, “In the Natu pass incident, Chinese causalities were estimated unofficially as 600 and Indian losses as at least half of that.” In total 47 Gallantry awards were bestowed on the Indian troops who fought at Nathu La. Major General Sagat Singh proved to the adversary that the Indian Army was unyielding. The myth of Chinese invincibility was wrecked.

On the evening of 3 December 1971, Pakistani aircraft attacked Indian airfields. Immediately General Sam Manekshaw, the Chief of Army Staff, ordered the commanders to put into effect their operational plans. The war to liberate Bangladesh was underway.

On the sixth day of the war, Thursday, 9 December 1971, Lt General Sagat, corps commander of the IV Corps, stood on the east bank of river Meghna in East Pakistan visualising the unimaginable. At the planning stage, Lt General Sagat envisaged that the capture of Dacca (Dhaka now) was the key to winning the 1971 war. But Indian Generals remained sceptical about Dacca as a military objective since two rivers protected it. The top brass in the operations room were impressed with Lt General Sagat’s daredevil capturing of towns and he had kept the enemy off-balance. He was credited for capturing Chandpur single-handedly. For his bosses his role in the War of 1971 was over.

On that very cold winter morning of 9 December, Lt General Sagat thought otherwise. From his perspective the only thing that stood between the Indian Army and absolute victory was the 4,000 feet wide Meghna river. The Pakistan Army had strategically destroyed the Ashuganj link the solitary bridge that spanned one of the broadest rivers in the region.

Boarding an Indian Air Force helicopter Lt General Sagat undertook a dangerous reconnaissance mission. Over Bhiarab Bazar his chopper was targeted by very accurate machine gun fire by the Pakistani troops. Bullets narrowly missed Lt General Sagat’s forehead. The main windshield shattered and the splintering glass injured him. The pilot received serious bullet wounds. The copilot managed to return to base despite sixty-five hits. The Army doctors dressing Lt General’s arm and forehead insisted that he take rest for twenty-four hours before resuming command. But the Lt General who had narrowly escaped death many times before immediately embarked on another mission in a chopper and returned to lead his men into the battlefield. Then in an astounding “helibourne operation” Lt General Sagat accomplished the impossible. Under his command on the night of 9-10 December, the squad of brave pilots of the fourteen IAF Mi4 choppers flew 110 sorties. Using the element of surprise Group Captain Chandan Singh magnificently airlifted the entire 311 Brigade with 23 troops in each flight. Simultaneously, 73rd Brigade moved across Meghna on boats and riverine crafts.

The next day USS Enterprise and the US Seventh Fleet were poised to enter the Bay of Bengal. At that crucial time, Lt General Sagat, with 3,000 troops and forty tonnes of equipment and heavy guns, was strategically positioned on the western bank of the mighty Meghna. Ahead of them lay the gates of fortress Dacca and the road to victory. The message that Lt General Sagat and his men had reached the other side of Megna was delivered in the office of the Prime Minister of India in distant New Delhi. It has been recorded that on hearing the news, Indira Gandhi beaming with joy and with wind in her hair ran across the corridor of her office. The Prime Minister personally commended Lt General Sagat and sent congratulatory messages to the Indian forces now racing towards Dacca.

Few notable moments can change the outcome of any war. The crossing of the Meghna by the Indian Air Force and Army was the most important and decisive operation in the Bangladesh War. The dare and dash initiative of the field commander that smashed its way through the pride of the Pakistani Army was a major factor in India’s triumphant march towards Dacca.

On the 12th day of the war the first artillery shell of the Indian Army fell inside the Dacca cantonment. Pakistan’s Marshal Law Administrator Lt General Abdullah Khan Niazi, the man behind the “impregnable fortress Dacca strategy”, had in an impromptu press conference at Dacca airport promised to fight to the “last man, last round”. But within hours Lt General Niazi reached the breaking point.

On Thursday, 16 December 1971, a date that will live in infamy in Pakistan, a supremely confident Lt General Sagat was introduced to the grim faced Lt General Niazi at the Race Course in Dacca. The Pakistani commander is reported to have exclaimed in admiration, “Oh my God, you accomplished the inconceivable.”

At 1631 hours, on the darkest day in Pakistan’s history, Lt General Niazi borrowed a pen from Surojit Sen of All India Radio and signed five copies of the Instrument of Surrender. Lt General Jagjit Singh Arora accepted the surrender on behalf of India. No words were exchanged. There was nothing left to be said. That Instrument of Surrender was the first and the only public surrender in world history. Simultaneously 93,000 Pakistani officers, soldiers, civilian officials, and allies laid down their arms. This was a feat unparalleled in the annals of warfare. It was the fastest successful military campaigns of modern times and the swiftest liberation of a nation ever.

This was a defining moment in modern India’s history.

In the celebrated blackand-white photograph of that evening, the strikingly handsome Lt General Sagat Singh can be seen standing directly behind Lt General Niazi and between Vice Admiral N. Krishnan, Air Marshal H.C. Dewan and Lt General Jack Jacob.

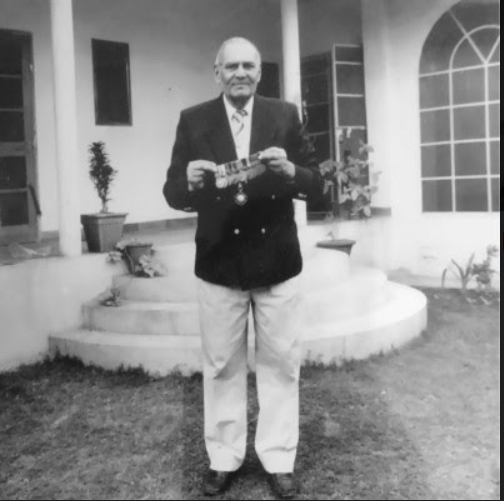

In 1972, Lt General Sagat Singh, PVSM, was awarded the Padma Bhushan and in March 2013 the Government of Bangladesh acknowledged his achievements. After retirement from the Indian Army he settled down in Jaipur and appropriately named his house “Meghna”. On 26 September 2001, thirty years after ensuring the victory in the Bangladesh War, our nation’s war hero who changed the history and geography of India breathed his last.

Lt General Sagat Singh, PVSM, Padma Bhushan (14 July 1919 to 26 September 2001), arguably the greatest combat general of the contemporary world, was a remarkable Indian. An effort should be undertaken by the Government of India to include his wartime exploits in school textbooks. And finally on the eve of the golden anniversary of the Bangladesh War this outstanding combat leader is the right candidate for the Bharat Ratna.

Bhuvan Lall is the author of ‘The Man India Missed The Most Subhas Chandra Bose’ and ‘The Great Indian Genius Har Dayal.